6. WILLEM JANSZOON - FIRST EUROPEAN TO REACH AUSTRALIA?

But he's not impressed with what he sees.

Map of the voyage of Willem Janszoon in 1605–1606. By Lencer - "own work", used: Australia discoveries by Europeans before 1813 de.png by User:LencerGeneric Mapping Tools and SRTM30http://www.australiaoncd.com.au/discovery/duyfken_chart.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11764166

This is Part 6 in the series, ‘Who really discovered Australia?’ Become a free or paid subscriber to Michael’s Curious world for full access to reports, the archive of past stories, my ‘Newbies Guide to Substack’, my gratitude and to help keep the journey going. Only $6 a month or a 30% discount of $50 a year.

CONTENTS:

Janszoon reaches the Gulf of Carpentaria

Janszoon not impressed with what he saw

Aboriginal account of Janszoon’s visit

Conflict breaks out

Janszoon continues exploring

Janszoon visits again

WILLEM JANSZOON deserves a lot more attention in the history of Australia.

Janszoon and his crew aboard the Duyfken in 1606 became the first Europeans confirmed to have encountered the northern Australian mainland, which the indigenous residents called Marege.

Europeans had long speculated about the existence of a hypothetical southern continent they called Terra Australis (Latin: 'Southern Land'), first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that continental land in the northern hemisphere should be balanced by land in the southern hemisphere.

This theory of balancing land has been documented as early as the 5th century on maps by Macrobius, who used the term Australis on his maps.

Other names for the hypothetical continent have included Terra Australis Ignota, Terra Australis Incognita ("the unknown land of the south") or Terra Australis Nondum Cognita ("the southern land not yet known") and the Portuguese Jave le Grande.

Other European names were Brasiliae Australis ("the southern Brazil"), and Magellanica ("the land of Magellan). In medieval times it was known as The Antipodes. The separate seventh continent was not named Antarctica until the 1890s.

But Janszoon (c. 1570 – c. 1630, sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz.) actually found the sixth continent.

That’s assuming the Portuguese didn’t actually get here first, and noting the visits by the Makassans and the initial arrival of humans from Timor about 65,000 years ago, as discussed earlier in this series.

Janszoon was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor who served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 1603–1611 and 1612–1616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of Solor.

They sailed from the Netherlands for the East Indies for the third time on 18 December 1603, with Janszoon as captain of the Duyfken (or Duijfken, meaning 'Little Dove'), one of twelve ships of a fleet.

Janszoon reaches the Gulf of Carpentaria

From Java, he was sent exploring and, on 18 November 1605, Duyfken sailed from Bantam to the coast of western New Guinea and crossed the eastern end of the Arafura Sea into the Gulf of Carpentaria, without being aware of the existence of Torres Strait.

Duyfken was actually in Torres Strait in February 1606, a few months before Spanish explorer Luis Vaez de Torres sailed through it, resulting in it being named Torres Strait..

On February 26, 1606, Janszoon made landfall at a river on the western shore of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland, near the modern town of Weipa.

Janszoon named the river R. met het Bosch, but it is now known as the Pennefather River. This was the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent.

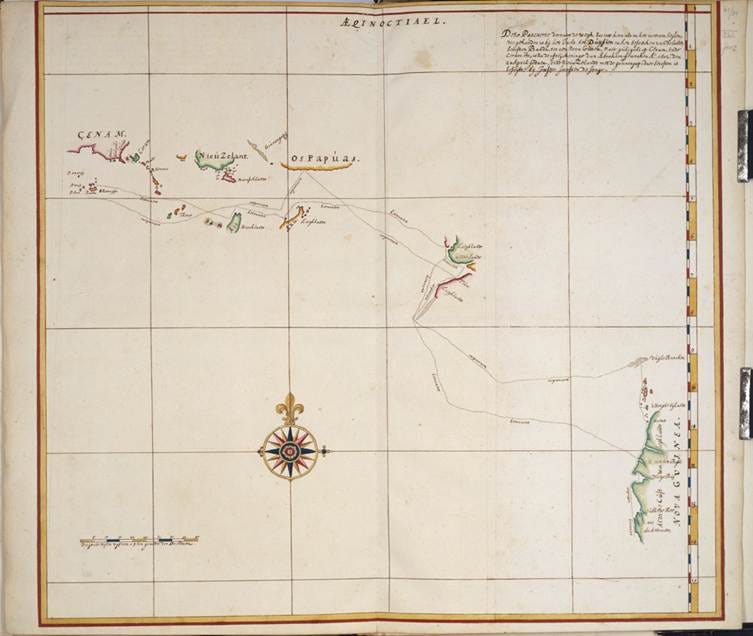

1670 copy of the map drawn on the Duyfken.

Janszoon proceeded over Albatross Bay to Archer Bay, the confluence of the Archer and the Watson Rivers, which he named Dubbelde Rev (lit. 'double river') and then on to Dugally River, which he named the Visch (lit. 'fish').

He charted some 320 kilometres of the coastline, which he thought was a southerly extension of New Guinea.

Janszoon not impressed with what he saw

According to the Dutch East India Company’s later instructions to Tasman, Janszoon found:

‘ … that vast regions were for the greater part uncultivated, and certain parts inhabited by savage, cruel black barbarians who slew some of our sailors, so that no information was obtained touching the exact situation of the country and regarding the commodities obtainable and in demand there.’

Finding the land swampy and the people inhospitable (ten of his men were killed on various shore expeditions), Janszoon decided to return at a place he named Kaap Keerweer (lit. 'Cape Return', the name persist as Cape Keer Weer), south of Albatross Bay, and arrived back at Bantam in June 1606.

Aboriginal account of Janszoon’s visit

Cape Keer Weer is on the lands of the Wik-Mungkan Aboriginal people, who today live in or near the Aurukun Mission Station. Remarkably, there is an indigenous record of Janszoon’s visit in the book Mapoon, written by members of the Wik-Mungkan people and edited by Janine Roberts, which contains an account of this landing passed down in Aboriginal oral history:

‘The Europeans sailed along from overseas and put up a building at Cape Keerweer. A crowd of Keerweer people saw their boat sail up and went to talk with them. They said they wanted to put up a city. Well, the Keerweer people said that was all right. They allowed them to sink a well and put up huts. They were at first happy there and worked together. The Europeans gave them tobacco. They carried off the tobacco. They gave them flour—they threw that away. They gave them soap, and they threw away the soap. The Keerweer people kept to their own bush tucker.’ From Mapoon, Janine Roberts. 1.

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janszoon_voyage_of_1605%E2%80%931606

Conflict breaks out

According to this account, some of Janszoon's crew angered the local people by raping or coercing women into having sex and by forcing men to hunt for them, so the locals killed some of the Dutch and burned some of their boats.

The Dutch are said to have shot and killed many of the Keerweer people before escaping. However, events from a number of different encounters, over many years, with Europeans may have been combined in these oral traditions.

Janszoon continues exploring

Janszoon retraced his route north to the north side of Vliege Bay, which Matthew Flinders called Duyfken Point in 1802.

He then passed his original landfall at Pennefather River and continued to the river now called Wenlock River. This river was formerly called the Batavia River, due to an error made in the chart made by the Carstenszoon 1623 expedition.

According to Carstenszoon, the Batavia River was a large river, which in 1606, "the men of the yacht Duijfken went up with the boat, on which occasion one of them was killed by the arrows of the natives".

There is documented evidence suggesting that during Janszoon’s voyage the Dutch landed near Mapoon and on Prince of Wales Island, with the map showing a dotted trajectory line to that island, but not to Cape Keer Weer.

Janszoon called the land he had discovered Nieu Zelant, or Nieu Zeelandt, after the Dutch province of Zeeland, but the name was not adopted, and was later used by Dutch cartographers for New Zealand.

Duyfken replica on the Swan River in Perth 2006. By Lencer - "own work", used:Australia discoveries by Europeans before 1813 de.png by User:LencerGeneric Mapping Tools and SRTM30http://www.australiaoncd.com.au/discovery/duyfken_chart.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11764166

Janszoon visits again

Janszoon made a second voyage and reported that on July 31, 1618, he had landed on an island at 22° South with a length of 22 miles and 240 miles south-southeast of the Sunda Strait.

This is believed to have been the peninsula from Point Cloates to North West Cape on the Western Australian coast, which Janszoon presumed was an island without fully circumnavigating it.

Janszoon’s log was lost, but his charts survived and were incorporated into various maps, including a 1622 map which was the first to show an actual part of the Australian coastline. He later became an Admiral, fought the British and Chinese, and died in 1830 aged 60.

Luís Vaz de Torres (born c. 1565; fl. 1607)

Luis Váez de Torres (Spanish spelling), was a 16th- and 17th-century maritime explorer and captain of a Spanish expedition. 1.

He made the first recorded European navigation of the strait that separates the Australian mainland from the island of New Guinea, and which now bears his name of Torres Strait.

Torres entered the Spanish Navy and went to its South American vice-royalties. He first appeared in the historical record as the nominated commander of the second ship in an expedition to the Pacific proposed by the Portuguese-born navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, searching for the elusive ‘Terra Australis’.

A party of three Spanish ships, San Pedro y San Pablo (60 tons), San Pedrico (40 tons) and the tender Los Tres Reyes Magos left Callao in Spanish Peru on 21 December 1605, with Torres in command of the San Pedrico.

In May, 1606, they reached a group of islands that would later be known as the New Hebrides and Vanuatu.

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lu%C3%ADs_Vaz_de_Torres

First use of name ‘Austrialia’

In May, 1606, they reached a group of islands that would later be known as the New Hebrides and Vanuatu. Queirós named the group La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo: "Austrialia [sic] of the Holy Spirit". Austrialia was a reference to the Austrian origins of the House of Habsburg to which the Spanish Royal family belonged. The largest island in Vanuatu is still known officially by the abbreviated form, Espiritu Santo.

Along with the ancient Latin name Terra Australis, Queirós's word Austrialia has often been regarded as one of the bases of the name of Australia, which was popularised by the explorer Matthew Flinders from 1804, and it has been in official use since 1817.

Disaster struck when Queiros’ crew mutinied at sea, claiming they had been badly-treated, and sailed away to Mexico, so Torres took command of the remaining expedition.

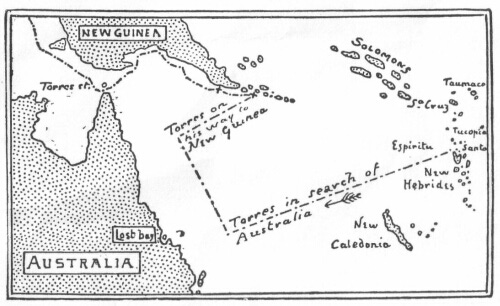

Torres’ expedition. By Holger Behr - own work, route from various biografis, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2054999

Torres takes charge

On June 26, 1606, the San Pedrico and Los Tres Reyes Magos under Torres’ command set sail for Manila in The Philippines, but winds prevented the ships taking the more direct route along the north coast of New Guinea.

They sighted land on July 14, 1606, probably the island of Tagula, south-east of New Guinea. The voyage continued over the next two months along the south-eastern coast, and a number of landfalls were made to replenish the ships’ food and water.

The expedition discovered Milne Bay including Basilaki Island which they named Tierra de San Buenaventura, taking possession of the land for Spain in July, 1606.

They had violent contacts with local indigenous people. Twenty people were captured, including a woman who gave birth several weeks later.

Torres stayed close to the New Guinea coast to navigate the 150-kilometre strait that now bears his name. They reached Orangerie Bay, which Torres named Bahía de San Lorenzo because he landed on 10 August, the feast of Saint Lawrence or San Lorenzo.

Torres’ route near Australia. By Public domain map from Project Gutenberg Australia, [1] - follow the 'map' link for the explorer., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2118314

Torres’ route went very close to the tip of Cape York, but he never claimed to have seen the mainland, only islands, so it is unclear if he actually sighted Cape York, before turning for Manilla. He came so close.

An account of the voyage was written by the second in command, Diego de Prado, with charts, and signed by Torres, but disappeared into the Spanish archives for a long time.

A copy is believed to have reached Sir Joseph Banks and been passed on to Captain James Cook. The State Library of NSW acquired a copy in 1932.

NEXT: A rush of obscure explorers reaches Australia. You will never have heard of most of them, but there stories are interesting.