4. MAKASSANS EXPLORE 'WILD COUNTRY'

Trading and fishing across 'Marege' wild country in northern Australia

One of the ships in Borobudur depicting a double-outrigger vessel with tanja sails in bas-relief (c. 8th–9th century). By Michael J. Lowe, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2097218

‘Who Really discovered Australia?’ investigates the curious history of how the world’s elusive sixth continent and largest island Sahul remained unknown for so long - or did it? We are up to Part 4 and, after 65,000 years of human migration, the Europeans still haven’t even arrived yet.

Become a free or paid subscriber for full access to reports, to the archive of past stories and to my ‘Newbies Guide to Substack’ for just $6 a month or $50 annually, a 30% discount.

CONTENTS:

Visiting ‘Marege’

Matthew Flinders meets Pobasso

Baudin also meets Makassans

Continuing links

Makassan relics found

MACASSAN (or Makassan) people from Sulawesi are believed to have fished and traded across the wild northern Australia for at least 500 years.

While some sources say the Makassans began visiting the coast of Northern Australia about 1720, radiocarbon dating studies of Yolgnu Aboriginal rock art suggest dates as early as the 1500s and a Sulawesi historian has argued for 1640.

They came with the monsoon season in December, established themselves at points along thousands of kilometres of coastline, fished, and boiled and dried trepang, staying about four months, before returning home to sell the trepang to Chinese merchants.

Model of Makassan perahu, Islamic Museum of Australia. By Resnjari - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99445686

Visiting ‘Marege’

Makassans came first to the Kimberley region and later to Arnhem land in the Northern Territory. There is even a Macassan Beach in East Arnhem Land.

They called the area ‘Marege’ meaning ‘wild country’, ranged thousands of kilometres along Australia's northern coasts and also fished in West Papua, Sumbaya, Timor and Selayar.

Their trade with indigenous people included cloth, tobacco, metal axes and knives, rice, gin, turtle-shell, pearls and cypress pine and some indigenous people were employed as trepangers.

Trepang, also known as sea cucumber or beche-de-mer in French, is a marine invertebrate, which was collected at low tide by hand or spear, for sale to Chinese merchant fleets, which had traded down the coast of Asia for a long time.

Trepang is still prized by the Chinese for its culinary value, medicinal properties or as an aphrodisiac.

Relations between Makassans and Aboriginal people in northern Australia have been studied extensively. It appears there were negotiations about where the Aborigines would allow the Makassans to fish and gather trepang, with the Makassans making payments to the indigenous residents. 1

A Makassan term for trepang, taripan, became tharriba, jarripang or darriba in Aboriginal languages on the Cobourg Peninsular.

Makassan perahu or praus could carry a crew of thirty members and the total number of trepangers arriving each year may have been about one thousand.

The Makassan crews established themselves at various semi-permanent locations on the coast, to boil and dry the trepang before the return voyage home, four months later.

Matthew Flinders meets Pobasso

Matthew Flinders made a record of how trepang was processed when he met Pobasso (or Probasso or Pobassoo), a chief of a Makassan fleet of six vessels, on February 17, 1803, at the English Company’s Islands Malay Road, now Nhulunbuy, north of Arnhem Land.

Flinders initially thought they were Chinese pirates, which is interesting in itself as it shows Flinders expected to meet Chinese ships off the coast of northern Australia.

He soon discovered they were friendly. Pobasso, who Flinders described as a ‘short, elderly man’ and five others came aboard Flinders’ ship The Investigator.

They were able to communicate through Flinders’ cook, Abraham Williams, who was Javanese. A crew member, William Westall, made a drawing of Pobasso.

By William Westall - National Library of Australia, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54829201

Pobasso told Flinders their fleet commander was named Salloo and the fleet was owned by ‘the Rajah of Boni’. Boni was modern Brunei.

The entire fleet was 60 perahu with 1000 crew, about 20-25 on each ship.

Pobasso had made six voyages to Australia over 20 years, but did not know of any European settlement in Australia, and was interested to learn about Port Jackson (Sydney).

Pobasso’s son took notes ‘in foreign characters, writing from right to left’. Arabic and Hebrew are written right to left.

The fleet had no charts or navigational tools except for a small compass. The vessels carried a month’s supply of water, dried fish, coconuts, rice and poultry.

Pobasso carried two small brass guns, obtained from the Dutch, and the men carried daggers. He said the fleet sometimes had skirmishes with the natives and he had once been speared in the knee.

Flinders gave Pobasso gifts of iron tools and a letter in English to show to any other ships he met. Flinders also named Pobasso Island after him.

A character named Pobasso appears in the novel ‘The Bunting Quest’ by Steven Marcuson and the play ‘The Cucumbers’ by Chris James.

Baudin also met Makassans

French explorer Nicolas Baudin also encountered a fleet of 26 perahu off the coast of Northern Australia in the same year 1803 as Flinders.

There are written and oral accounts of Aboriginal people moving to Macassa with Asian fishermen, some dating back as far as the 1600s.

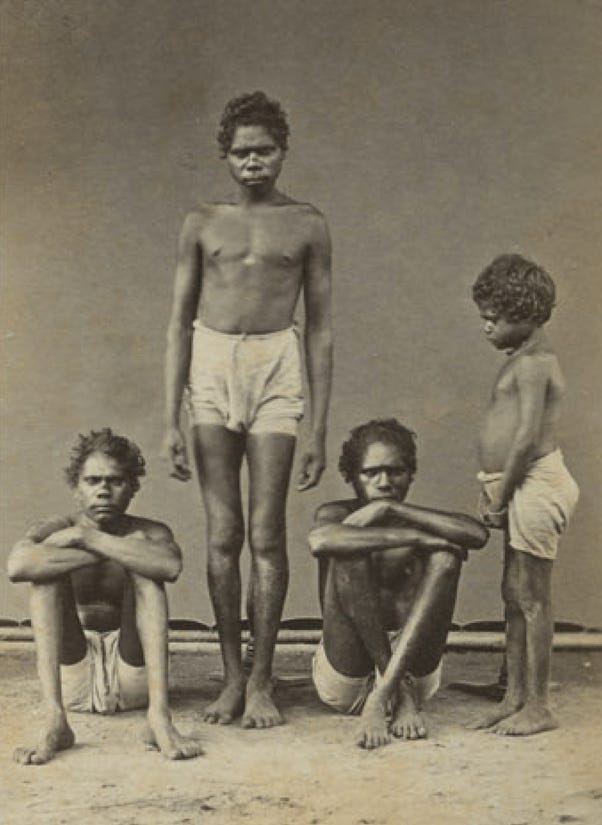

Italian botanist Odoardo Beccari took photographs of Aboriginal Australians in Makassar in 1873.

A group of Aboriginal Australians in Makassar, 1873. By Odoardo Beccari - https://janelydon.wordpress.com/2020/10/07/photographing-macassan-australian-histories/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=154895393

Continuing links

The British settlements of Fort Dundas and Fort Wellington were established as a result of Phillip Parker King’s contact with Makassan trepangers in 1821.

Macassan words appear in the Yolgnu language, including rupiah (money), jama (work), and balanda (white person). Muslim references also appear in Dreamtime stories.

In 2012, a huge painting by Gulumbu Yunupingu titled Garrurru was installed at the Australian National University. Garrurru is the Yolngu word for ‘sail’ and derives from the Makassan word for sailcloth.

In 1988, the prau Hati Marege (‘Heart of Marege’) made a voyage from Makassar to Arnhem Land coinciding with the Australian Bicentenary.

A female figure outlined in beeswax over painting of a white Makassan prau. By Unknown (Australian) - 3wEM5uNnPs5NMA at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22942270

Both the dug-out canoes and shovel-nosed spears found in Arnhem Land were based on Makassan prototypes. Yolngu communities also learned ironworking techniques from the Makassans, which allowed for the manufacture of the canoes and spears.

Smallpox may have been introduced to northern Australia in the 1820s via Makassan contact.

Macassan perahu. By Courtesy Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19405406

Makassan relics found

Archaeological remains of Makassan processing plants from the 18th and 19th centuries are still at Port Essington, Anuru Bay and Groote Eyelandt, along with stands of the tamarind trees introduced by the Makassans.

Excavations have revealed pieces of metal, broken pottery and glass, coins, fish-hooks and broken clay pipes.

A swivel gun found at Dundee Beach near Darwin in January 2012 may be from Makassar, as may two bronze cannons found on a small island in Napier Broome Bay, on the northern coast of Western Australia.

Relations with Makassans were cited as part of a native title claim to exclusive sea rights surrounding Croker Island, and the High Court of Australia partially granted the claimants' requests, providing the communities with non-exclusive sea rights in 2001.

Current Australian attempts to prevent Indonesian fishermen from fishing in northern Australian waters fly in the face of the history of Makassans fishing those waters since at least the 1600s, if not earlier.

NEXT: The Portuguese arrive in Southeast Asia, but did they reach Australia?