Junks in Guangzhou, photograph c. 1880 by Lai Afong. By Lai Afong - caviarkirch, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38325399

This is‘Who Really Discovered Australia?’ , a deep-dive into the history of the search for and exploration of the elusive sixth continent Sahul. Become a free or paid subscriber to Michael’s Curious World for only $6 a month or save 30% by subscribing for only $50 annually and support this curious journey. Interesting. Surprising. Fun.

SAILING ships traded around the Southeast Asian region for thousands of years before Europeans arrived, so why didn’t they notice Australia?

Surely someone must have run into that huge island continent? How could they miss something so big for so long? Maybe they did see it, but we don’t have records of those accidental encounters.

Much of what is known about contacts from across the Asian region with the Australian landmass comes from European sources, meaning it is certain to be incomplete.

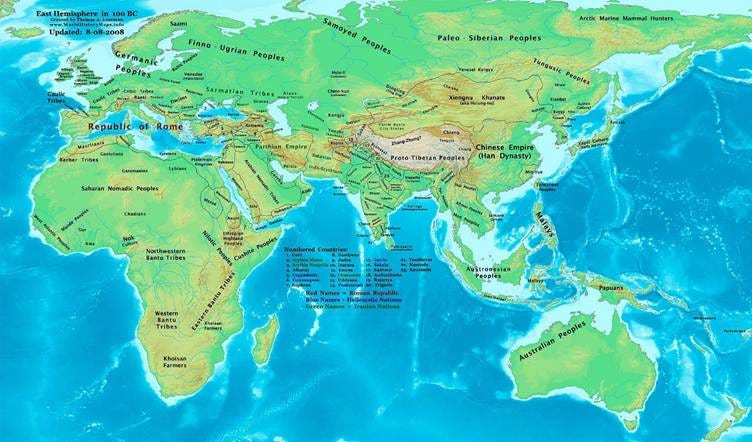

Asia in 100 BCE, showing the Saka and their neighbors. By Thomas Lessman (Contact!) - self-made (For reference information, see below), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4019403

K'un-lun po (also called Kun-lun po, Kunlun po, or K'un-lun bo) were ancient sailing ships from maritime Southeast Asia, described by Chinese records from the Han dynasty (206BC – 220AD).

These ships connected trade routes between Africa, the Middle East and India with Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines and north to China and Japan. Ships of this type were still in use until the 14th century.

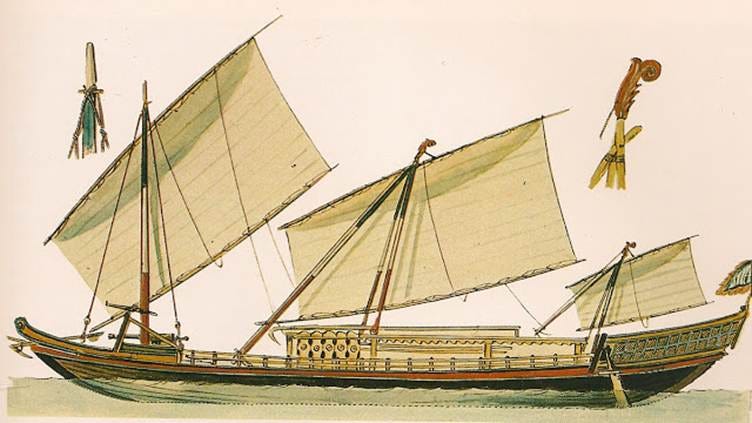

They were more than 50–60m long, displaced up to 3000 tons, the hull was made of multiple planks, had many masts and sails, the sail was in the form of a tanja sail and the planks were stitched with plant fibres.

Faxian (Fa-Hsien) in his return journey to China from India (413–414) embarked on a ship carrying 200 passengers and sailors from K'un-lun which towed a smaller ship. There are also accounts of attacks by fleets of ships from the Kalinga Kingdom of Java on Champa (Cambodia) in 774 and 787AD, while Pingzhou Ketan by Zhu Yu made between 1111 and 1117 AD mentioned sea-going ships of Java which could carry several hundred men. Indian historians describe large ships called Colandia and Kolandiaphonta (Kun-lun po) used for voyages from the ancient port of Puhar to the Pacific Islands.

A lanong with three tanja sails of the Iranun people of the Philippines. By Rafael Monleón - Historia gráfica de la navegación y de las construcciones navales en todos los tiempos y en todos los países (1890), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70514738

Greek astronomer Ptolemy said in his work Geography (ca. 150 AD) that huge ships came from the east of India. This was also confirmed by an anonymous work called Periplus Marae Erythraensis. Both mention a type of ship called kolandiaphonta (also known as kolandia, kolandiapha, and kolandiapha onta), which is a transcription of the Chinese word K'un-lun po—meaning ‘ships of Kun-lun’. A 260 CE book by K'ang T'ai, quoted in Taiping Yulan, (982 AD) described ships with seven sails called po or ta po (great ship or great junk) that could travel as far as Syria.

The Borobudur ship (Samudra Raksa) seen from the front, expanding its sails like a swan (goose-winged/running before the wind, receiving wind from aft). By Phillip Beale (photograph)Yusi Avianto Pareanom (book)Publisher: Kementerian Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata (Ministry of Culture and Tourism) - Pareanom, Yusi Avianto (2005). Jalur Kayu Manis, Ekspedisi Kapal Samudraraksa Borobudur. Yogyakarta: Kementerian Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=119531499

Asian history is filled with numerous city-states which rose and fell, sometimes dominating their neighbours and at other times being dominated by them.

Examples are Ayutthaya in Thailand, the capital of the Kingdom of Siam and a prosperous international trading port from 1350 until razed by the Burmese in 1767, and Java in what is now Indonesia, a powerful kingdom known for shipbuilding.

Batavia became the capital of the Dutch East Indies from 1619 until 1949. Many of the ships trading between Asia and Europe touched the coastline of Western Australia. Indian kingdoms also rose and declined in power, becoming trading centres.

China had its ‘Silk Road’ across the land links to Baghdad, but other trade and contacts flourished along the entire Asian coast from China down through modern countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia and Indonesia, and also with India, the Middle East and Africa.

By the Song dynasty (c. 960 to 1279), China had adopted ocean-going technologies from Southeast Asian trade ships, including Tanja sails (tilted square or rectangular) and fully-battened (long strips of wood to support the sail). Similar designs were also adopted by other East Asian countries including Japan.

Seven voyages of Admiral Zheng He

The best-known examples of Chinese influence in the region are the seven voyages of Chinese Admiral Zheng He (birth name Ma He) between 1405 and 1433.

Want to read more? Become a paid subscriber to Michael’s Curious World.

Statue from a modern monument to Zheng He at the Stadthuys museum in Malacca City, Malaysia. By Photo: Marcin Konsek / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51927875

Zheng, a Muslim, followed well-established trade routes and had accurate maps. Although mostly peaceful, they expected tribute to be paid to China, sank pirates and fought a land war in Ceylon. Zheng’s fleets did not reach Australia, but demonstrated how close Chinese influence came to this continent.

Voyages of Zheng He. By SY - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65379957

The fleets were enormous, both in the number and size of the ships. The first fleet, which departed on 11 July, 1415, consisted of 317 ships and 28,000 crewmen. Zheng's largest ships were almost twice as long as any wooden ship ever recorded, including nine-masted treasure ships up to 127 metres long, and each carried hundreds of sailors on four decks. Warships were smaller and faster.

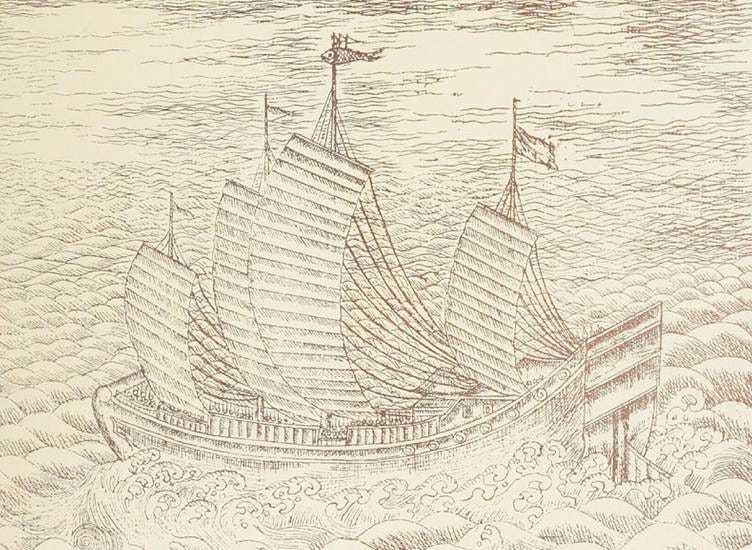

An image of seagoing junk, identified as Cheng Ho (Zheng He)'s treasure ship in Mills, J. V. G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan: 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores' [1433]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 30. Excerpt: The illustration appearing in the present volume (Fig. 2) is reproduced from a book by M. Medard; but it has not been possible to ascertain the origin, and it may be modern. It purports to show one of Cheng Ho's sea going ships, and, since it has four masts, it was presumably about one hundred and fifty feet [48.8 m] long.

Their purpose was to establish a Chinese presence and impose imperial control over the Indian Ocean trade, impress foreign peoples and extend the empire's tributary system, with countries sending wealth to China.

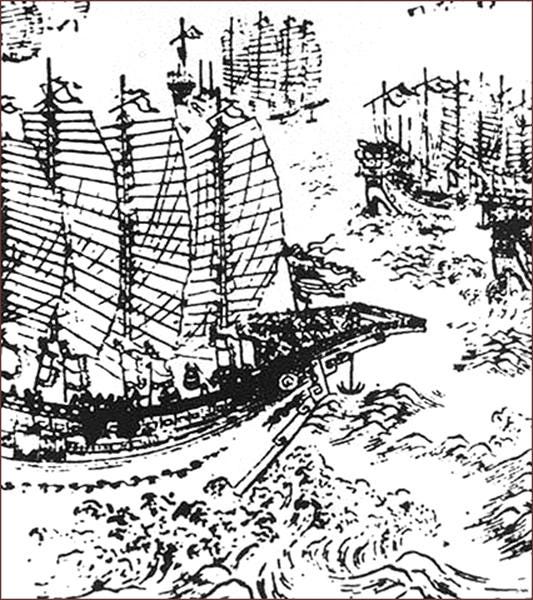

Early 17th-century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships By Wubei Zhi武備志, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=289739

Zheng He's fleets visited Brunei, Java, Siam (Thailand), Southeast Asia, India, the Horn of Africa, and Arabia. Zheng He presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain and silk and received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, ivory and even a giraffe.

The voyages spread Chinese populations and culture. Today, 5.5% of Australians have Chinese ethnic identity, the highest percentage of Chinese in any country outside Asia.

NEXT: The Makassans sail across the north of the continent, fishing and trading with the indigenous residents, well before the arrival of the first Europeans.