Toussaint Antoine DE CHAZAL DE Chamerel - Portrait of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN, 1774-1814 - Google Art Project. By Antoine Toussaint de Chazal - XQFjQ8PX1C_hwA at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23601763

‘Who Really Discovered and Explored Australia’ is an in-depth dive into the search for the elusive sixth continent and its early exploration.

Become a subscriber for full access to reports, to the archive of past posts, to my ‘Newbies Guide to Substack’ and to support this curious journey of discovery.

Flinders first reaches Australia

Captain Matthew Flinders was an extremely important explorer who circumnavigated and named Australia.

Flinders (1774 – 1814) was a Royal Navy officer, navigator and cartographer who led the first inshore circumnavigation of mainland Australia, accompanied by George Bass and a famous cat named Trim.

He is also credited as being the first person to utilise the name Australia to describe the entirety of that continent including Van Dieman’s Land (now Tasmania), a title he regarded as being "more agreeable to the ear" than previous names such as Terra Australis.

Flinders was involved in several voyages of discovery between 1791 and 1803, the most famous of which are the circumnavigation of Australia and an earlier expedition when he and George Bass confirmed that Van Diemen's Land was an island.

Flinders joins Bligh

In May, 1791, Midshipman Flinders joined Captain William Bligh’s expedition on HMS Providence transporting breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica It was Bligh's second "breadfruit Voyage", following his ill-fated voyage on HMS Bounty.

They arrived at Adventure Bay on the eastern coast of Bruny (original French name Bruni) Island off the south-eastern coast of the island now known as Tasmania in February 1792.

The officers and crew spent over a week in the region obtaining water and lumber, and interacting with local Aboriginal people. There nis a local monument to the visit. It was Flinders' first association with any of the land which is now part of Australia.

After the expedition arrived in Tahiti in April, 1792, and obtained the many breadfruit plants to take to Jamaica, they sailed back west. Instead of travelling via Adventure Bay, Bligh navigated to the north of the Australian continent, sailing through the Torres Strait.

Fighting natives

Off Zagai Island, they were involved in a naval skirmish with armed local men in a flotilla of sailing canoes, which resulted in the death of several Islanders and one crewman. The expedition returned to Jamaica and England in 1793.

After serving in the war with France, Flinders enlisted as a midshipman aboard HMS Reliance in 1795, headed to New South Wales carrying the new Governor Captain John Hunter. Flinders became friends with the ship's surgeon George Bass, who was three years his senior.

Exploring around Port Jackson

HMS Reliance arrived at Port Jackson in September 1795, and Bass and Flinders soon organised two expeditions in open boats named Tom Thumb I and II. First, they sailed with a boy, William Martin, to Botany Bay and up the Georges River.

In March 1796, again with William Martin, they sailed south from Port Jackson, but were soon forced to beach at Port Kembla, where two Aboriginal men piloted the boat to the entrance of Lake Illawarra, where they were able to dry their gunpowder and obtain supplies of water from another group of Aboriginal people.

Flinders gets his own ship

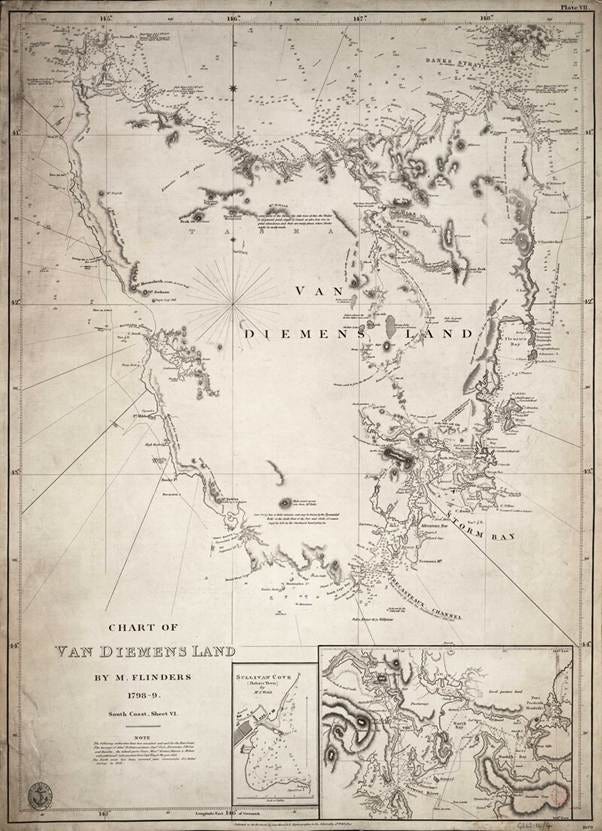

In 1798, Flinders, then a lieutenant, was given command of the sloop Norfolk, with orders "to sail beyond Furneaux’s Islands, and, should a strait be found, pass through it, and return by the south end of Van Diemen’s Land.’

Flinders, with Bass and several crewmen, sailed the Norfolk along the uncharted northern and western coasts of Van Diemen's Land, rowed up the Derwent River at modern Hobart, rounded Cape Pillar and returned to Furneaux's Islands.

He completed the circumnavigation of Van Diemen's Land and confirmed the presence of a strait between it and the mainland. The passage was named Bass Strait and the largest island in the strait would later be named Flinders Island.

Chart of Van Diemen's Land produced by Matthew Flinders; it is now called Tasmania. By Flinders, Matthew; Hydrographic Office; Thomas Hurd - http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/540614, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61685056

Flinders heads north

In 1799, Flinders was given approval to explore the coast north of Port Jackson, again in the Norfolk. They departed on July 8, 1799, and arrived in Morton Bay (now Brisbane) six days later.

Flinders rowed ashore at Woody Point and named a point two miles (3.2 km) west of that ‘Redcliffe’ (on account of its red cliffs). That point is now known as Clontarf Point while the name ‘Redcliffe’ is used by the town to the north.

He landed on Coochiemudlo Island on July 19 while searching for a river in the southern part of Moreton Bay, while to the north, Flinders explored a narrow waterway which he named the Pumice Stone River, now called the Pumicestone Passage, climbed Mt Beerburrum and continued north to Hervey Bay, before returning south.

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined Reliance and returned to Britain.

Flinders given command of Investigator

Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc., used his influence to convince the Admiralty of the importance of an expedition to chart the coastline of New Holland.

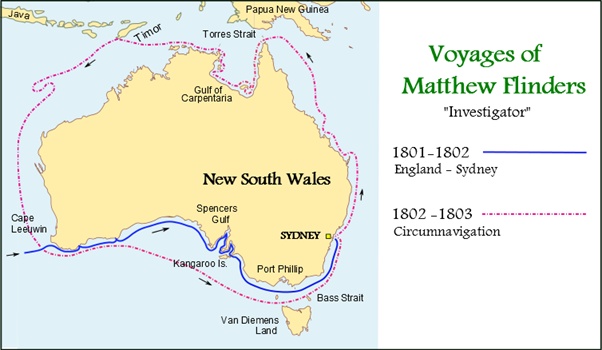

Flinders was given command of HMS Investigator, a 334-ton sloop, and promoted to Commander. Investigator set sail for New Holland on July 18, 1801.

The voyages of Flinders aboard HMS Investigator.

Investigator reached and named Cape Leeuwin on the south of Western Australia on December 6, 1801, surveyed the southern coast of the mainland and anchored in King George Sound for a month.

The local Aboriginal people initially indicated that Flinders' group should "return from whence they came", but relations improved. In nearby Oyster Harbour, Flinders found a copper plate that Captain Christopher Dixson on Elligood had left the previous year.

Approaching Port Lincoln, eight of the crew were lost when the sailing cutter capsized. Flinders named nearby Memory Cove in their honour.

Naming Kangaroo Island

On March 21, 1802, the expedition reached a large island where many kangaroos were sighted. Flinders and some crew found the animals so tame they could walk right up to them.

They killed 31 kangaroos with Flinders writing that "in gratitude for so seasonable a supply [of meat], I named this southern land Kangaroo Island." The seals on the island proved less docile, with a crew member receiving a severe bite.

Meeting Baudin

Sailing east on April 8, 1802, Flinders sighted Geographe, commanded by the French explorer Nicolas Baudin. Flinders and Baudin exchanged details of their discoveries, despite believing their countries were at war.

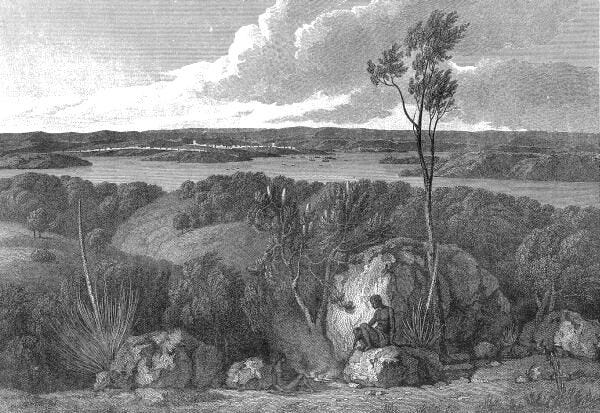

Flinders named the bay in which they met Encounter Bay. Flinders also explored Port Phillip (the future Melbourne), which, unknown to him, had been explored only ten weeks earlier by John Murray aboard HMS Lady Nelson, and returned to Port Jackson.

View of Port Jackson taken from the South by William Westall; engraving from Flinders’ A Voyage to Terra Australis, published in 1814.

Heading north again

Bungaree, an Aboriginal man who had accompanied Flinders on his earlier coastal survey in 1799, and another local Aboriginal man named Nanbaree, joined the expedition, while Captain Murray and the Lady Nelson would accompany the Investigator as a supply ship.

Flinders set sail again on July 22, 1802, heading north and surveying the coast of what would later be called Queensland.

They anchored at Sandy Cape where, with Bungaree as mediator, they feasted on porpoise blubber with a group of Batjala people.

In early August, Flinders sailed into a bay he named Port Curtis, where the local people threw stones and Flinders ordered muskets be fired above their heads to disperse them.

Blocked by the Great Barrier Reef

Navigating north became increasingly difficult as they entered the Great Barrier Reef, which Flinders called ‘Barrier Reefs’ in his 1814 book.

The Lady Nelson was too unseaworthy to continue and Captain Murray sailed her back to Sydney with his crew and Nanbaree.

Flinders exited the reefs near the Whitsunday Islands and sailed north to the Torres Strait, arriving at Murray Island on October 28, where they traded iron for shell necklaces.

Conflict with Aborigines

The expedition entered the Gulf of Carpentaria on November 4 and charted the coast to Arnhem Land. At Blue Mud Bay the crew, while collecting timber, had a skirmish with local Aboriginal men and one of the crew received four spear wounds while two of the Aboriginal men were shot dead.

At nearby Caledon Bay, Flinders took a 14-year-old boy named Woga captive to coerce the local people to return a stolen axe, which was not returned, but Flinders released the boy who had spent a day tied to a tree.

Meeting Makassans

The expedition encountered a Makassan trepanging fleet captained by a man called Pobasso on February 17, 1803, near Cape Wilberforce, and exchanged information. (See Part 4. Makassans explore ‘wild country’.)

Much of the Investigator was rotten and Flinders decided to complete the circumnavigation of the continent without any further close surveying of the coast, sailing to Port Jackson via Timor and the western and southern coasts of Australia.

He jettisoned two wrought-iron anchors which were found by divers in 1973 at Middle Island, Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia. Back at Port Jackson on June 9, 1803, Investigator was judged to be unseaworthy and condemned.

Heading for England

Unable to find another vessel, Flinders set sail for Britain as a passenger aboard HMS Porpoise, but the ship was wrecked on Wreck Reefs in the Great Barrier Reef. Flinders navigated the ship's cutter across open sea back to Sydney, and arranged for the rescue of the remaining marooned crew.

Then Flinders took command of the 29-ton HMS Cumberland to return to England, but the poor condition of the vessel forced him to put in at French-controlled Isle de France (now known as Mauritius) for repairs on December 17, 1803, just three months after Baudin had died there.

A prisoner in Mauritius

Although Britain and France were at war, Flinders thought the scientific nature of his work would ensure safe passage, but he was arrested and remained there for more than six years.

Among the papers seized from the ship were British Government documents and three logs of the Investigator, of which only volumes one and two were returned to Flinders and are now both held by the State Library of NSW. The third volume was later deposited in the Admiralty Library and is now held in The National Archives (United Kingdom).

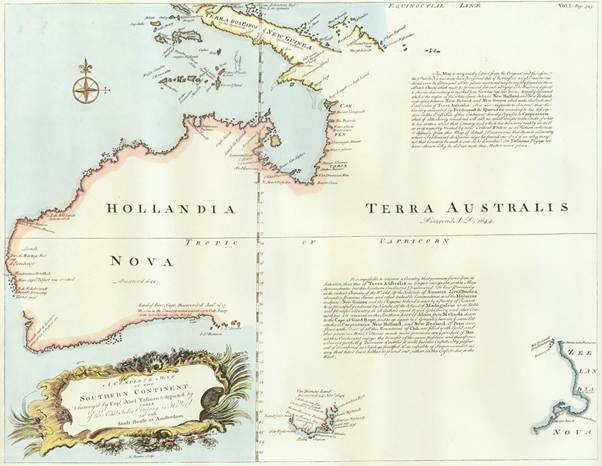

In captivity, Flinders recorded details of his voyages for future publication and put forward his rationale for naming the new continent 'Australia' as an umbrella term for New Holland and NSW – a suggestion taken up later by Governor Macquarie. Flinders made a map using the name "Australia or Terra Australis" for the title instead of ‘New Holland’.

Death in England

In June, 1809, the Royal Navy began a blockade of the island, and a year later Flinders was released, but his health had suffered and although he returned to Britain in 1810, he died, aged 40, on July 19, 1814, from kidney disease and did not live to see the success of his widely praised book and atlas, ‘A Voyage to Terra Australia.’

The very long full title of Flinders book, including a synopsis, was ‘A Voyage to Terra Australis: undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803 in His Majesty's ship the Investigator, and subsequently in the armed vessel Porpoise and Cumberland Schooner. With an account of the shipwreck of the Porpoise, arrival of the Cumberland at Mauritius, and imprisonment of the commander during six years and a half in that island’.

Terra Australis renamed Australia

Flinders is credited with causing the name Australia to be adopted. He was not the first to use the name ‘Australia’, but he was the first to apply it to the whole continent. He explained his reasons in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks:

‘The propriety of the name Australia or Terra Australis, which I have applied to the whole body of what has generally been called New Holland, must be submitted to the approbation of the Admiralty and the learned in geography. It seems to me an inconsistent thing that captain Cooks New South Wales should be absorbed in the New Holland of the Dutch, and therefore I have reverted to the original name Terra Australis or the Great South Land, by which it was distinguished even by the Dutch during the 17th century; for it appears that it was not until sometime after Tasman's second voyage that the name New Holland was first applied, and then it was long before it displaced T’Zuydt Landt in the charts, and could not extend to what was not yet known to have existence; New South Wales, therefore, ought to remain distinct from New Holland; but as it is requisite that the whole body should have one general name, since it is now known (if there is no great error in the Dutch part) that it is certainly all one land, so I judge, that one less exceptionable to all parties and on all accounts cannot be found than that now applied.

Banks wrote a draft introduction to Flinders’ book in which he said:

‘It was not until after Tasman's second voyage, in 1644, that the general name Terra Australis, or Great South Land, was made to give place to the new term of New Holland; and it was then applied only to the parts lying westward of a meridian line, passing through Arnhem's Land on the north, and near the Isles St Peter and St Francis on the south: All to the eastward, including the shores of the Gulph of Carpentaria, still remained Terra Australis. This appears from a chart by Thevenot in 1663, which he says "was originally taken from that done in inlaid work upon the pavement of the new Stadt House at Amsterdam". It is necessary, however, to geographical precision that the whole of this great body of land should be distinguished by one general term, and under the circumstances of the discovery of the different parts, the original Terra Australis has been judged the most proper. Of this term, therefore, we shall hereafter make use when speaking of New Holland and New South Wales in a collective sense; and when using it in an extensive signification, the adjacent isles, including that of Van Diemen, must be understood to be comprehended.’

In his Voyage, Flinders wrote:

‘There is no probability, that any other detached body of land, of nearly equal extent, will ever be found in a more southern latitude; the name Terra Australis will, therefore, remain descriptive of the geographical importance of this country, and of its situation on the globe: it has antiquity to recommend it; and, having no reference to either of the two claiming nations, appears to be less objectionable than any other which could have been selected.

…

Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into Australia; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.’

1744 Chart of Hollandia Nova – Terra Australis by Emanuel Bowen.

Flinders had married his longstanding friend Ann Chappelle (1772–1852) on April 17, 1801, but was prevented from taking her to Port Jackson and she did not see him for nine years. They had one daughter.

The location of Flinders’ grave had been lost by the mid-19th century, but archaeologists excavating a former burial ground near London's Euston Railway Station for a rail project announced in January, 2019, that his remains had been identified. On July 13, 2024, he was reburied in Donnington, Lancashire, the village of his birth.

Flinders’ legacy is huge and reflected in many monuments to him in Australia, the United Kingdom and Mauritius. Flinders never named anything after himself, but his name now appears in more than 100 places in Australia alone, including Flinders University and, fittingly, the frigate HMAS Flinders. Numerous books and articles have been written about Flinders, including one about his cat Trim, the first cat to circumnavigate Australia. How good is that!

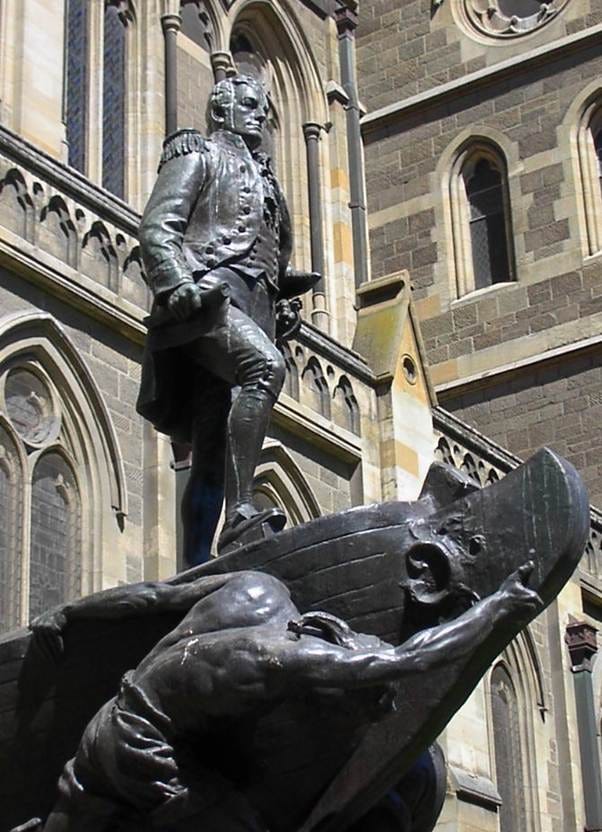

Statue of Flinders outside St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to MICHAEL'S CURIOUS WORLD to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.